Why Focus on WASH in Health Care Facilities?

The Ebola outbreak of 2014–2016 highlighted a two-fold danger of poor water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and infection prevention and control (IPC) in health care facilities (HCFs): an inability to prevent outbreaks, and the associated risk of contracting diseases in facilities themselves, known as health care-associated infections (HCAIs). The attention exposed glaring issues in the health system — a lack of skills, training and protocols for infection prevention; coordination challenges among “water” partners and entities; and a misperception that improving WASH infrastructure (such as building water points and bathrooms) alone improves WASH in HCFs.

It also catalyzed a desire to rapidly learn how best to improve these conditions.

As USAID’s flagship Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP), we worked to advocate for investments in WASH in HCFs, improve programmatic approaches, and contribute to global learning. This microsite includes a toolbox of resources as well as perspectives and an emerging approach from our experience integrating WASH in support of quality of care improvements that lead to improved health outcomes.

Despite a high associated risk for morbidity and mortality, WASH and environmental conditions in HCFs receive inadequate attention. And the lack of appropriate WASH facilities and practices within HCFs results in three primary consequences:

1. HCFs become unable to provide safe services (such as hygienic births and clean surgeries), especially to mothers, newborns and children.

2. Populations served by these facilities lack confidence in the institutions as clean, safe places to seek care.

3. Limited capacity to prevent, identify and contain disease outbreaks.

The establishment of clean and desirable HCFs is an essential component to achieving several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 3 — ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages — and SDG 6 — ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. National governments, donors and development partners in the WASH and health sectors can empower HCFs to make incremental WASH improvements and provide better quality of care for patients, especially mothers, newborns and children.

15.5% of patients develop one or more health care-associated infections during their stay.

Source: Allegranzi et al. 2011

The Changing Focus of WASH in HCF Programming

Donors, governments and implementing organizations have traditionally pursued an infrastructure-centric approach to improve WASH in HCFs, including the construction or repair of water supply, sanitation and waste management facilities (such as incinerators). The reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health community has traditionally focused on improving quality of care by pursuing infection prevention practices at HCFs.

With the Ebola outbreak of 2014-2016, IPC needs resulted in a vibrant, focused interest in WASH in HCF. Subsequent analysis — including WHO’s 2015 report identifying the poor WASH situation in HCFs globally and the high risk of HCAIs — has led to increased interest in the issues.

As a broader understanding of WASH in HCF has emerged, a more human-centered lens recognizes the critical role that facility management and behavior-centered programming play in achieving health outcomes. With lessons from past efforts informing the sub-sector, more comprehensive WASH approaches (including MCSP’s Clean Clinic Approach and WHO’s WASHFIT model) include:

• Establishing HCF WASH standards and routine monitoring systems.

• Building WASH technical and leadership capacity within the health system.

• Developing and implementing annual, incremental WASH improvement plans.

• Creating incentive and reward systems for performance, building on examples from USAID’s predecessor Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program.

• Elevating “cleaners” to frontline health worker status.

The WASH and health sectors increasingly recognize the needs to marry investments in WASH Infrastructure, IPC, and functional management systems to improve HCF cleanliness and maintain high-quality care.

WASH and Quality of Care

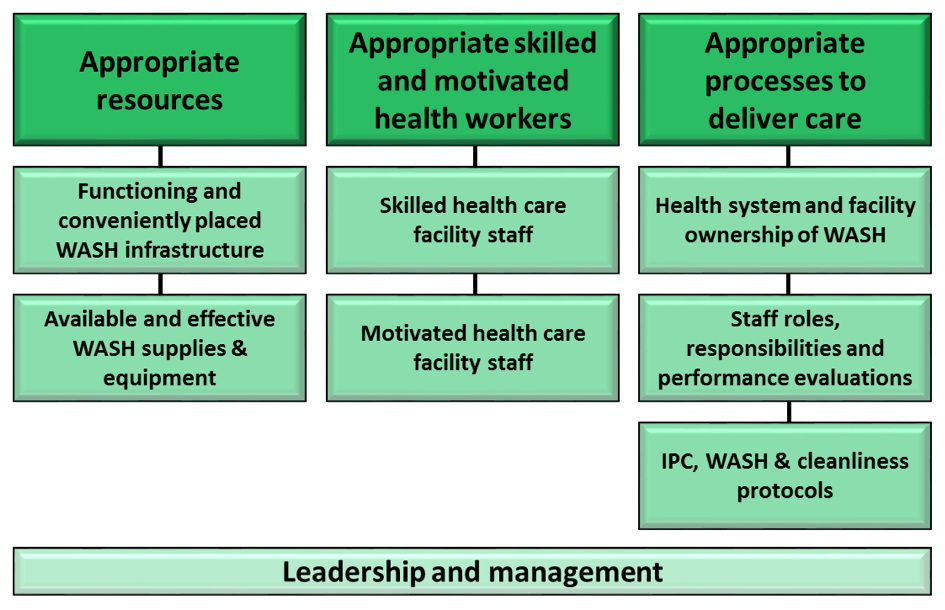

Quality of care improvements center on providing standardized care and improving the interaction between providers and patients. These improvements can be organized along three axes: resources, staff and processes. The framework below, adapted from the WHO’s Quality of Care framework and the USAID ASSIST Project, aligns WASH in HCF within the broader frame of quality improvement.

Past WASH interventions focused largely on the first two categories – resources (infrastructure) and staff (education and training) – while often neglecting the third improvement category: creating effective process-related interventions that improve WASH management, behaviors, and facility cleanliness. To improve the quality of IPC, MCSP has implemented the Standards-Based Management and Recognition approach in more than 100 HCFs in Program countries.

MCSP believed that WASH and IPC in HCF improvements are an essential component of high-quality care. Appropriate processes and management systems were their cornerstone, and WASH in HCF discussions focused on planning, design, implementation and measurement.

WASH is not the main barrier to seeking care, but patients frequently report being dissatisfied.

Source: Tessema et al. 2015

Components of Preventing Infections at HCFs

Many governments, organizations and universities are working to develop useful program and monitoring tools for WASH, IPC and health practitioners to make HCFs safer. Following the publication of the WHO and UNICEF’s report Water, sanitation and hygiene in health care facilities: Status in low- and middle-income countries and way forward, a global action plan was developed to advance WASH in HCF via four global task teams focused on advocacy, monitoring, research and facility improvements. WHO also has a technical unit focusing on IPC and a global IPC network with well-defined goals and objectives.

In parallel to the global working group’s activities, implementing partners experimented with various pieces – such as cleaners, IPC, waste management, water supply, and sanitation – to improve WASH in HCF. As a global integrated health program, MCSP had the unique experience implementing WASH to improve maternal, newborn and child health outcomes, and linking with cross-cutting quality improvement and health systems strengthening themes.

Infections account for 1.2 million neonatal deaths each year, and for 15% of maternal deaths.

Source: Black et al. 2010, Lawn et al. 2010

Video: Challenges and proposed solutions for advancing WASH in healthcare facilities.

Challenges & Recommendations for Implementation

While WASH programming has targeted child health extensively, why hasn’t it better addressed maternal and newborn health? In particular, what integration challenges might prevent more systematic WASH improvements in primary health care settings?

This question sat at the forefront of MCSP’s WASH program. We created this video to illustrate the critical challenges and offer solutions for improving the WASH sector’s role in primary health care, especially for mothers and newborns. A related MCSP brief proposes actions to address WASH challenges in maternal and newborn health at the HCF level.

In 2019, MCSP collaborated with the University of North Carolina’s Water Institute to conduct two reviews. The first was a review and gap analysis of critical environmental conditions in health within tools for improving the quality of care for mothers and newborns in health care facilities. The second review examined common and effective indicators for monitoring environmental health conditions and measuring improvements in maternal and newborn health care, and made recommendations to enhance monitoring of environmental health in maternal and newborn health care settings.

The Clean Clinic Approach

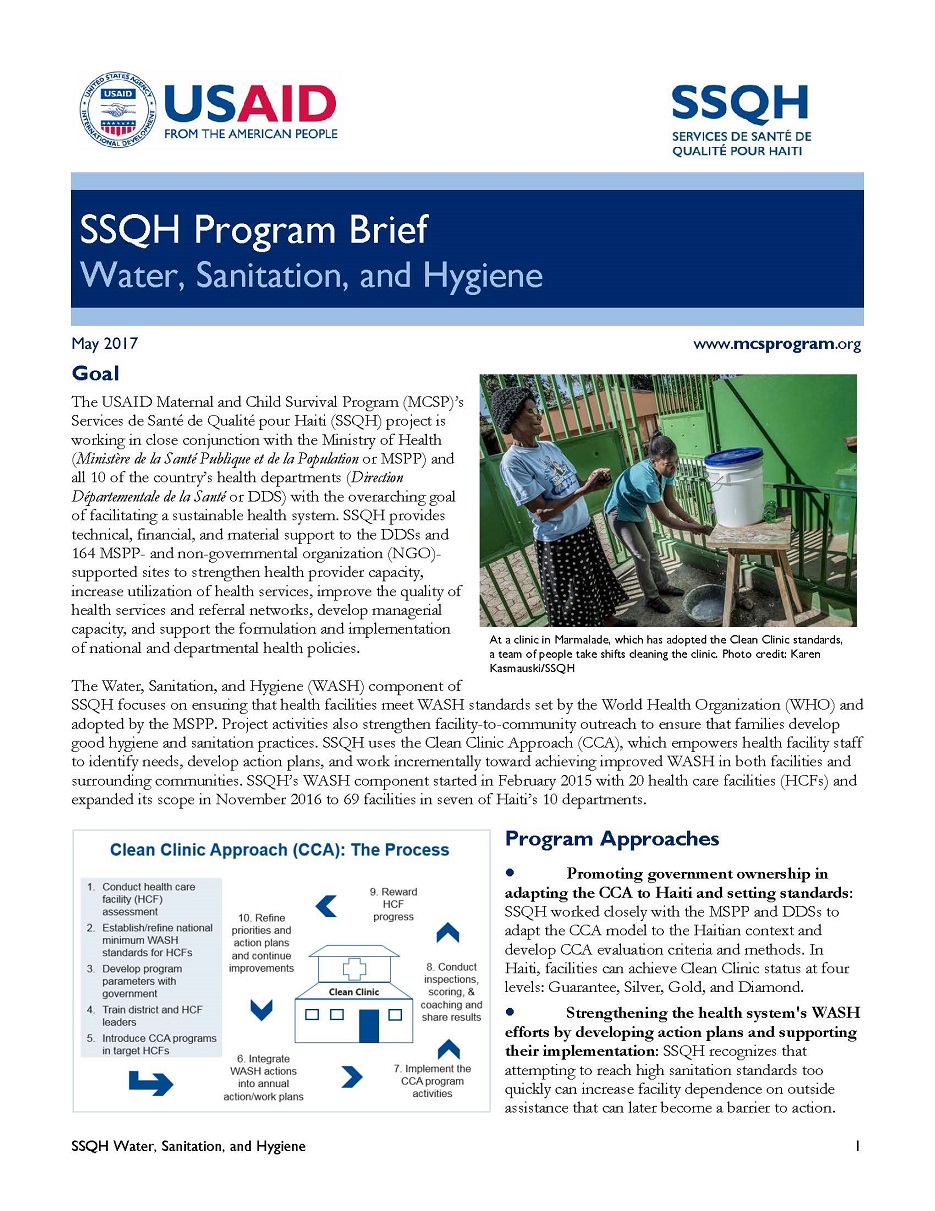

MCSP co-developed (with Save the Children) and tested its comprehensive Clean Clinic Approach. The approach seeks to ensure effective national coverage and empower local levels to improve existing WASH in HCF. (This video further explains the Clean Clinic implementation process.)

MCSP also published ward-level scorecards used for monitoring and certifying HCFs in Nigeria. Other useful resources for designing, implementing and monitoring WASH in HCF programs can be found on WHO’s WASH in HCF website. WASH in HCF tools found in WHO and UNICEF’s WASHFit toolkit

WASH in HCF tools found in WHO and UNICEF’s WASHFit toolkit also aim to help HCFs analyze problems, make improvements, and monitor their progress. These tools are useful guides when developing comprehensive WASH in HCF standards and tracking HCF progress against established standards – and can be easily integrated into the Clean Clinic Approach implementation process.

Video: The Clean Clinic Approach.

In data from 54 countries representing 66,101 facilities:

- 38% lacked an improved water supply

- 19% did not have improved sanitation

- 35% had no water and soap for handwashing

Source: WHO/UNICEF. 2015

MCSP Country Highlights

As USAID’s flagship maternal and child health program, MCSP became a central mechanism for delivering WASH-focused programming that supports stronger health services and better quality of care. The Program implemented the Clean Clinic Approach in DR Congo, Guatemala, Haiti and Nigeria, but also conducted more limited WASH and infection prevention improvements in Guinea, Ghana and Liberia.

For an overview of our Clean Clinic work across countries, download our report on supporting quality of care improvements through WASH in four countries. For detailed information on our country programs, please refer to the country sections below.

Haiti

In Haiti, MCSP designed and piloted the Clean Clinic Approach, beginning as a 19-facility pilot in 2015 and expanding to 69 facilities in 2017. Working through the Ministry of Public Health and Population (MSPP), the approach ensures that facilities meet MSPP WASH in HCF standards. In 2016, Hurricane Matthew tested the Haitian health system’s capacity for response and recovery: in areas where the Clean Clinic Approach had trained personnel on WASH in HCF, health services rebounded more quickly and efficiently. Despite this devastating emergency, by the end of the two-year Clean Clinic Approach program, all 69 participating HCFs demonstrated progress, improving their “clean clinic scores” by an average of 22 points from baseline to endline (100 point scale).

DR Congo

In DR Congo, showers and latrines have been cleaned and fenced in.

In DR Congo, MCSP worked with the MoH’s Office of Hygiene and Public Safety to develop their own version of the Clean Clinic Approach (Centre de Sante Assaini). By the end of MCSP activities, 35 HCFs had an average Clean Clinic Approach score increase from 39% to 70% between the first and last assessments. For a full case study brief on MCSP’s Clean Clinic activities in DR Congo, click here. Our DR Congo Clean Clinic video can be viewed here.

Nigeria

In 2017, MCSP partnered with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to undertake a multi-phase study in Nigeria investigating the behavioral barriers and motivators to practicing appropriate hygiene during the highest risk period for both newborn sepsis and puerperal sepsis in mothers (from the onset of labor through the first two days of life). The first phase of the study included a global literature review, scoping visit, and key informant interviews with global and national stakeholders. The second phase was an observational and qualitative study that elucidated barriers, motivators and potential improvements to practicing appropriate hygiene behaviors during the highest risk period. Peer-reviewed journal publications on the phase II study results can be found here and here.

Following phases I and II, MCSP designed and implemented a pilot activity to improve WASH and infection prevention within MCSP-supported HCFs. A final report on the full three-phase activity can be found here. Clean Clinic monitoring and certification scorecards for HCFs, labor & delivery wards, and postnatal care wards can be found here, along with special considerations for special newborn care wards. Hygiene and infection prevention promotional products are also available.

Guatemala

In 2018, MCSP collaborated with the Ministry of Health in Guatemala to pilot the Clean Clinic Approach in 11 secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities offering labor & delivery services in the Western Highlands. After nine months of coaching and supervision visits using standardized tools, each HCF was evaluated across three wards (emergency/general, labor & delivery, and postnatal) in seven technical domains (water, sanitation, hygiene, sterilization, waste management, cleaning, administration and wastewater).

All 11 HCFs improved their average emergency ward Clean Clinic scores, from 41 points at baseline to 87 points at endline (100 point scale). Within labor & delivery wards, the average score increased from 50 to 91 points. Within postnatal care wards, the average score increased from 46 to 90 points.

For more details on MCSP’s Clean Clinic work in Guatemala, visit our report on Supporting Quality of Care Improvements through Water, Sanitation & Hygiene: MCSP Implementation Experiences in Four Countries. Additionally, a retrospective cost analysis on the Clean Clinic activities can be found here. A full program case study is pending formal journal publication.

For a summary of MCSP’s Clean Clinic Approach implementation experiences across countries, please visit our report: Supporting Quality of Care Improvements through WASH: MCSP Implementation Experiences in Four Countries.

The Way Forward

WASH in HCF improvement programs have registered promising initial successes, but several sustainability challenges remain:

Government Ownership and Investment: For WASH in HCF improvements to continue and sustain, governments need to prioritize and own that WASH services and cleanliness are essential components of providing high-quality patient care and achieving national health targets. Because MoHs are responsible for health outcomes, they must assume ownership of WASH in HCF by: establishing WASH and cleanliness standards; investing in WASH improvements; integrating WASH standards and responsibilities into pre-service and in-service trainings; integrating WASH in routine facility monitoring systems; and linking health sector staff performance to fulfillment of WASH functions. These changes will require budget shifts to include WASH improvements at national and local levels. As owner of WASH in HCF, MoHs will need to convene coordination efforts with other relevant ministries.

Prioritize Staff Motivation: Staff motivation is a critical element to drive and sustain change, especially where resources are limited. That motivation can come in many forms. Validating all HCF staff members is vital to improving WASH in HCFs. In particular, staff who do not provide direct patient care (such as cleaners and guards) can be included in meetings, planning sessions, and budgeting. Under the Clean Clinic Approach, training, supervision and coaching serve as key motivators for staff, and local government engagement is critical to success.

Community Engagement and Accountability: As the Clean Clinic Approach demonstrates, WASH in HCF change can happen by creating competition and accountability; when HCF staff know they are being “graded,” they perform better. Under the Clean Clinic Approach, this accountability mechanism is created through government inspections. However, what happens when governments do not perform this function or when the budget is insufficient? The community, as recipients of quality care, can also play a role. Inclusion of community members on HCF management teams can ensure community needs are represented, and serve as an accountability feedback loop between the community and the facility.

For countries and USAID missions considering WASH in HCF programming, MCSP had the proven technical experience and knowledge to support the development of national programs, pilot programs, and full-scale implementation of the Clean Clinic Approach. MCSP replicated its Clean Clinic Approach in Guatemala while also supporting several USAID priority countries with WASH in HCF needs.

Learn More

Contributors

Steve Sara

MCSP WASH Senior Specialist

Katrin DeCamp

MCSP Senior Communications Specialist

Joel Bobeck

Jhpiego Senior Web Designer

Embed videos courtesy of MCSP.

Photos courtesy of: Kate Holt/Jhpiego; Karen Kasmauski/MCSP + MCHIP + Jhpiego; Save the Children; Jhpiego.